Swimming in Circles - Tricking Sui's Mysticeti-C into Forfeiting Liveness

In this post we'll look at a flaw in Mysticeti-C's liveness proof that can potentially prevent the chain from committing new blocks, resulting in a chain halt.

The contents builds on the foundational concepts introduced in Consensus Primer, especially the definitions of safety, liveness, network synchrony assumptions, GST, and key security properties such as quorum intersection. If you’re not already familiar with these ideas, we recommend checking out that article first for a quick refresher.

With that groundwork laid, let’s dive into today’s topic.

DAG-based Consensus

Sui's Mysticeti-C is a DAG-based consensus algorithm. Before diving into its details, let’s start with the obvious question — what exactly are DAG-based consensus algorithms?

Sui's Mysticeti-C builds upon a rich family of DAG-based consensus research, from the early designs like Hashgraph, Aleph, and DAG-Rider to more recent protocols such as Tusk and Bullshark. The earliest DAG-based consensus algorithm Hashgraph is built for Asynchronous Networks, and adopted an extremely unstructured approach which rids the algorithm of leaders. Subsequent works reintroduced leaders, though with roles distinct from those in traditional chain-based consensus. More recently, Bullshark retrofitted DAG-based consensus algorithms to operate under Partially Synchronous Networks, while Sui's Mysticeti-C extends this line of work by pipelining leaders to further reduce finalization latency.

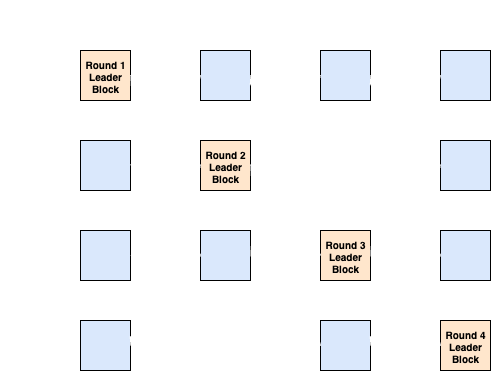

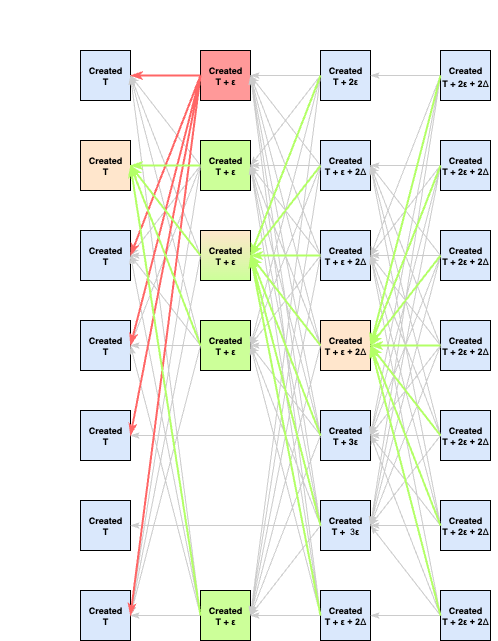

A typical pipelined DAG-based consensus algorithm looks like this:

Each validator produces blocks interlinked with other blocks to form a DAG.

Overall, DAG-based algorithms embody a few characteristics different from chain-based ones:

- The leader is no longer the sole entity responsible for proposing blocks. Instead, all validators continuously propose batches of transactions to be included in the ledger. The "leader" now serves merely as an "anchor", helping coordinate and finalize blocks rather than driving proposal itself

- Voting becomes "virtual". They're now derived implicitly from the DAG’s structure rather than occurring as a distinct phase of the protocol

These ideas sound abstract at first, and they are indeed difficult to grasp in isolation. To make them concrete, we’ll unpack each concept as we walk through Mysticeti-C’s algorithm.

Sui's Mysticeti-C

Mysticeti-C is a consensus algorithm designed by Sui, classified as a known

While Bullshark itself is a fascinating protocol deserving its own deep dive, we’ll set it aside here to keep this post concise. Similarly, we won’t cover Mysticeti-C’s reconfiguration mechanism, as it’s both non-trivial and orthogonal to our current discussion.

With that said, let's start with Mysticeti-C's terminologies.

Terminology

-

Supermajority: Supermajority refers to

of the total voting power -

Round: A monotonically increasing number associated with the consensus round. Each validator should create at most one block per-round

-

Leader: Validator(s) selected by some pre-determined scheduling algorithm

selectLeader(round). While all validators may produce block for each round, the blocks created by the leaders serve as anchors in finalizing blocks. The amount of leaders each round is configurable, but for this blog, we will assume there is only 1 leader per round. -

Slot: The pair of

(round, validator)is also called a slot, which uniquely identifies a position in the DAG. Slots are total ordered. More precisely -

Block: A proposal created by each validator in each round. It must include:

authorandround, which identifies theslotthe block belongs toparents, which define the block’s relationships and form the edges of the DAG- Must include a supermajority of blocks from the immediate previous round (

block.round - 1) - May contain additional blocks from even earlier rounds (

block.round - 1) - Must not contain more than one block from the same author

- For blocks created by honest validators,

block.parents[0]must be the latest block created byblock.author

- Must include a supermajority of blocks from the immediate previous round (

:: RUST1struct BlockHeader { 2 author: ValidatorId, 3 round: RoundId, 4 parents: Vec<BlockHash>, 5 ... 6} -

Leader / Anchor Slot: A slot where

slot.validatoris the leader forslot.round -

Leader / Anchor Block: A block affiliated with a leader / anchor slot

-

Wave Length: A configurable parameter representing the minimal round required to finalize a leader block. This parameter must

. For simplicity, all later visualizations assume -

Voting Round(

): , which is the round in which blocks cast their virtual votes on whether a leader block should be directly finalized -

Certificate Round(

): , which is the round in which blocks may gather votes for a leader block -

Link(

, ): A is said to have a link to if it can reach by traversing parent edges -

Virtual Vote(

, ): Voting round block votes for if - There is

is the first block affiliated with (multiple blocks may be affiliated to the same slot if equivocates) from 's point of view

To determine the first block affiliated with a slot from

's perspective, we perform a depth-first search over the parents vector and return the first block reached - There is

-

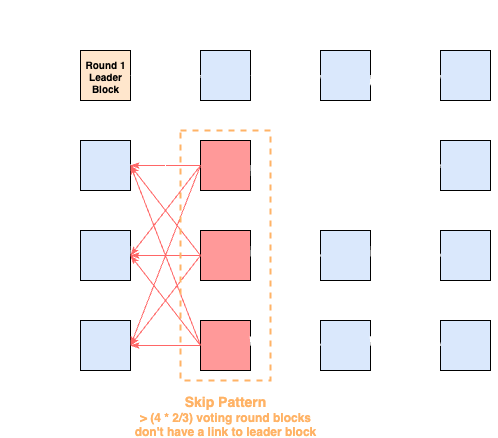

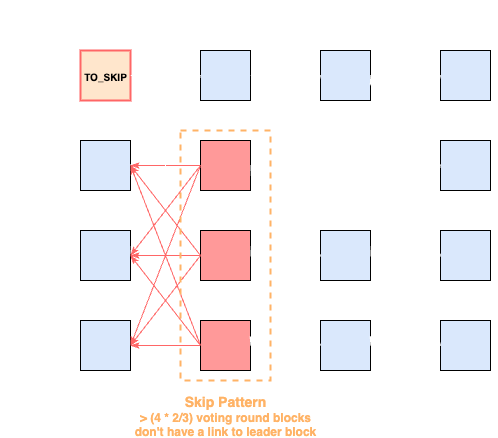

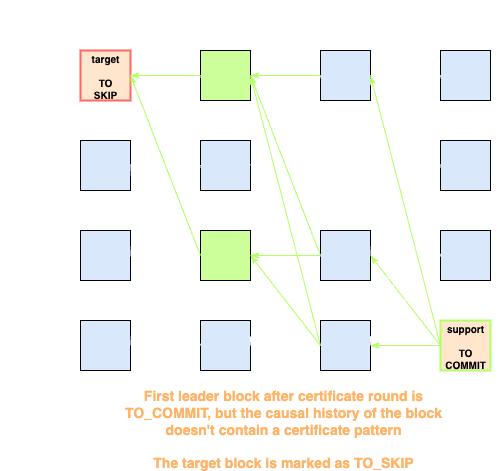

Skip Pattern: A validator observes a skip pattern for a

slotif it sees that a supermajority of voting-round blocks do not cast a vote for that slot’s leader

-

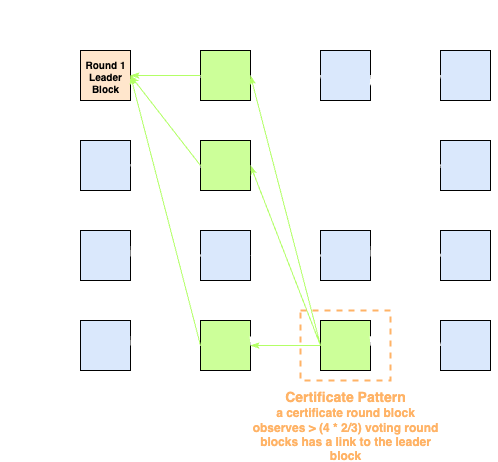

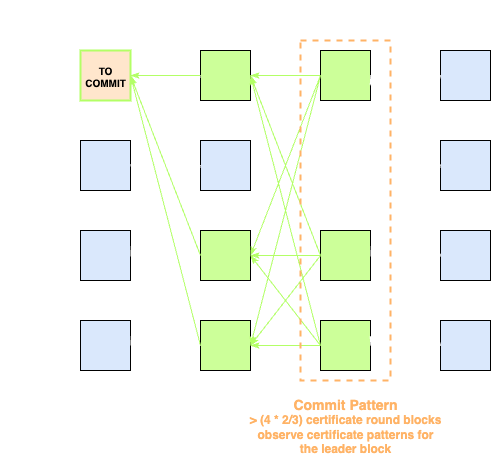

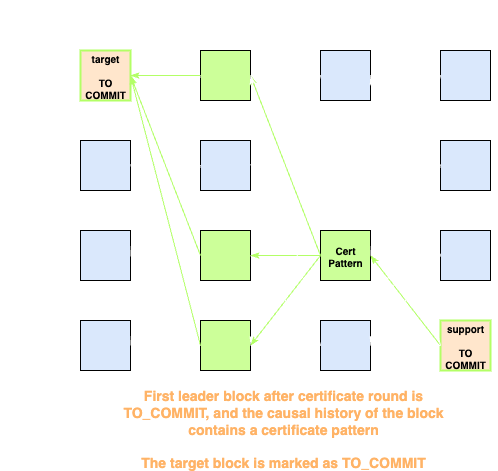

Certificate Pattern: A certificate pattern for a leader block is formed when a certificate-round block has a parent set containing a supermajority of voting-round blocks that voted for that leader

-

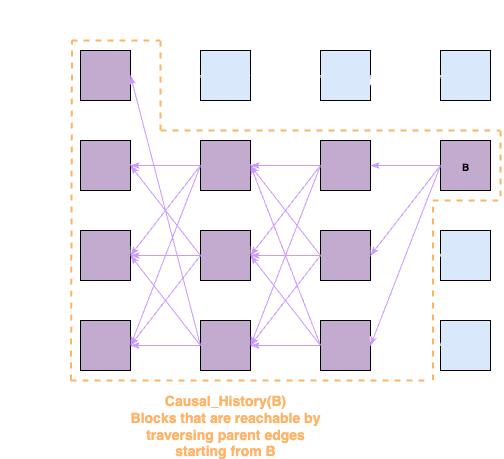

Causal History(

): The set of blocks reachable by traversing parentsedges starting from block

-

Commit: A leader block can be committed if its state is determined—either directly or indirectly—to be

Committable, and all preceding leader blocks have also had their states decided. The specific decision rules will be explained in later sections -

Finalize: A block (leader or non-leader) is finalized if it is included in the causal history of a committed leader block

Equivocation

By merging votes into blocks (i.e. virtualizing votes), DAG-based consensus algorithms reduce the ways validators may equivocate. There are mainly 4 ways for Sui's Mysticeti-C validators to equivocate:

- A validator refuses to propose a block when it should

- A validator proposes a block before it should, for example, before waiting for its timeout to expire

- A validator proposes more than 1 block for a

round - A validator sends its blocks to a certain set of validators while concealing it from the rest

While there are other ways to create invalid blocks to send to peers (e.g. a block that doesn't have sufficient parents), these cases are trivial to validate and will be immediately detected and rejected by honest validators upon receipt.

Algorithm

Sui's Mysticeti-C separates block production from block finalization.

Block production is relatively simple. Each validator keeps track of a local round number

The first time a validator collects blocks consisting of a supermajority of voting power from the previous round

Once a validator becomes ready, it must determine whether it should wait for a timeout. Specifically, it should wait for the following:

- The leader block for the first leader slot of round

to be received - If the validator has observed a leader block for the first leader slot

of round , it should also wait for a supermajority of round blocks that vote for a leader block associated with .

If both conditions are met, the validator will immediately create a new block, broadcast it, and move to the next round. Otherwise, it'll wait until the timer expires before giving up on the additional conditions.

For validators receiving new blocks, they must check the validity of each block before including it into the DAG. Since the validity of a block depends on the validity of its parents vector, this also means that a block can only be added to the local DAG of a validator after the entire causal history (excluding the block itself) is already included in the DAG.

:: PYTHON1TIMEOUT = 2 * Δ 2WAVE_LENGTH = 3 #configurable, must >= 3 3 4def receive_block(self, block): 5 # blocks should include block 6 blocks = self.request_missing_causal_history(block) 7 for entry in blocks: 8 if not self.validate_legal(entry): 9 return 10 for entry in blocks: 11 self.store.insert(entry) 12 if self.store.pending_round == block.round + 1: 13 self.try_propose(force = self.timeout) 14 15def try_propose(force = False): 16 pending_round = self.store.pending_round 17 prev_round = pending_round - 1 18 certified_round = pending_round - (WAVE_LENGTH - 1) 19 if not self.store.has_supermajority_blocks(prev_round): 20 return 21 if not force: 22 # wait for prev-round leader 23 if prev_round > 0: 24 slot = self.first_leader_slot(prev_round) 25 if not self.store.has_block(slot): 26 return 27 # wait for sufficient votes from voting round blocks 28 if certified_round > 0: 29 slot = self.first_leader_slot(certified_round) 30 if self.store.has_block(slot): 31 if not any( 32 [self.store.has_supermajority_votes(block) for block in self.store.get_blocks_by_slot(slot)] 33 ): 34 return 35 block = self.propose_new_block(pending_round) 36 self.store.pending_round += 1 37 self.reset_timer() 38 self.store.insert(block) 39 self.broadcast_block(block) 40 41def reset_timer(): 42 self.timeout = False 43 self.reschedule_timeout_handler( 44 time.now() + TIMEOUT, 45 self.timeout_handler 46 ) 47 48def timeout_handler(): 49 self.timeout = True 50 self.try_propose(force = True) 51 self.pause_timeout_handler()

The finalization algorithm is where things get a bit more convoluted. The algorithms works as follow. We first decide on the state (

The decision algorithm has two tracks, the direct decision rule and the indirect decision rule, to decide the state of a leader block.

Direct Decision Rule

The direct decision is relatively simple:

-

If the supermajority of voting round blocks for some leader slot does not virtually vote for it (skip pattern), then the leader slot can be marked as

-

If a supermajority of certificate round blocks each observes a supermajority of virtual votes to the leader block (certificate pattern), then the leader slot can be marked as

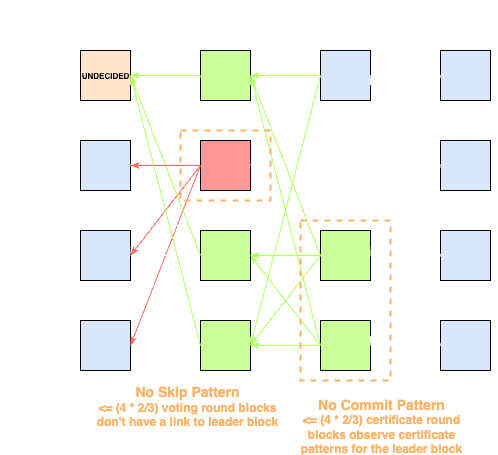

Of course, there are situations where neither decision can be made. This is where the indirect decision rule becomes useful, allowing the validator to retroactively determine the state of the leader slot.

Indirect Decision Rule

The indirect decision rule works as follows: the validator iterates through the decisions of all leader slots with

-

If

is , there isn't enough information for the validator to indirectly decide the state of , so we leave it in state until more information is obtained

-

If

is , we check if the causal history of contains a certificate pattern for any of the block in - If yes,

will be marked as

- If no,

will be marked as

- If yes,

Once the state of leader slots are decided, the next step is utilize these leader slots as anchors to finalize blocks. The algorithm works as follows:

- Iterate all leader slots in order

- If an

slot is encountered, we have to wait for it to be decided before moving forward, so stop the iteration - If a

slot is encountered, ignore it - If a

slot is encountered, collect all non-committed blocks included in the causal history of , sort them with some predefined sorting algorithm, then finalize each block in order

- If an

:: PYTHON1def receive_block(self, block): 2 ... 3 self.try_finalize_blocks(block) 4 5def try_finalize_blocks(self, block): 6 decisions = [] 7 last_decided_slot = self.last_decided_slot 8 for round in range(block.round, last_decided_slot.round - 1, -1): 9 for slot in self.deterministic_slot_ordering(round): 10 if not self.store.is_leader_slot(slot): 11 continue 12 (decision, block) = self.try_direct_decide(slot) 13 if decision is UNDECIDED: 14 (decision, block) = self.try_indirect_decide( 15 slot, 16 decisions 17 ) 18 decisions = [(decision, slot, block)] + decisions 19 for (decision, slot, block) in decisions: 20 if decision is TO_COMMIT: 21 self.finalize_causal_history(block) 22 else if decision is UNDECIDED: 23 break 24 self.last_decided_slot = slot 25 26def try_direct_decide(self, slot): 27 voting_round = self.voting_round(slot.round) 28 voting_round_blocks = self.store.get_blocks(voting_round) 29 if self.has_skip_pattern(slot, voting_round_blocks): 30 return TO_SKIP, None 31 else: 32 certificate_round = self.certificate_round(slot.round) 33 certificate_round_blocks = self.store.get_blocks(certificate_round) 34 for block in self.store.get_blocks_by_slot(slot): 35 # a validator may receive multiple blocks for the same round due to equivocation 36 if self.has_commit_pattern(block, certificate_round_blocks): 37 # no two equivocating blocks can both have a commit pattern 38 return TO_COMMIT, block 39 return UNDECIDED, None 40 41def try_indirect_decide(self, slot, decisions): 42 certificate_round = self.certificate_round(slot.round) 43 for (anchor_block, decision) in decisions: 44 if anchor_block.round <= certificate_round: 45 continue 46 if decision is UNDECIDED: 47 return UNDECIDED 48 else if decision is TO_COMMIT: 49 for block in self.store.get_blocks_by_slot(slot): 50 # a validator may receive multiple blocks for the same round due to equivocation 51 if self.has_certified_link(block, anchor_block): 52 return TO_COMMIT 53 return TO_SKIP 54 55def finalize_causal_history(self, block): 56 history = self.sort_blocks( 57 self.store.get_unfinalized_causal_history(block) 58 ) 59 for entry in history: 60 self.finalize_block(entry) 61 self.store.mark_finalized(entry)

Proof of Safety

Now that we've learned about the algorithm, it's time to discuss its security. Starting with safety, let's establish a few important properties:

-

DAGs owned by any two honest validators are graph consistent. Graph consistency means if a block

exists on any two DAGs and , then their causal history in both graphs must be identical This property is incorporates a few ideas. First, DAGs of different validators might not be identical. For example, validator A might have received a block while validator B hasn't yet (due to network latency of other reasons). However if a block

is observed by multiple honest validators, then their parent set must identical (else it won't be the same block). Recursively applying this rule, it's easy to see that the causal history, which is the subDAG spanned by the block and it's ancestors, must be identical. -

If the decisions of all leader slots are identical for two honest validators, then safety is satisfied

The reasoning is as follows: the leader slots on each validator is identical, and if the decision is also identical, then both validators must attempt to finalize blocks based on the same set of

. Because the algorithm guarantees slots are processed in order when considering block finalization, and because graph consistency guarantees that the causal history of each is identical, both validators will finalize the same set of blocks, in the same order. Thus, both agreement and total order are maintained, and therefore safety is guaranteed.

With these 2 properties, it's easy to see we only need to prove decisions on all leader slot state will be identical for any two honest validator. This can be further discussed in 4 parts:

-

For graph consistent DAGs

and , no slot can be marked as on , and directly marked as on Proof by Contradiction:

Assume a slot

is directly marked as on and indirectly or directly marked as on . A set of blocks on accounting for a supermajority of voting power from must not include any blocks for the slot in their causal history (skip pattern), and another set of blocks on accounting for a supermajority of voting power from must include in their causal history (certificate pattern). By quorum intersection,

and must overlap on at least one slot affiliated to an honest validator. Since - Honest validators create at most 1 block for each slot

- By graph consistency, no block can both include

in its causal history on , but not include it on , therefore

We have a contradiction, and the assumption cannot be true.

-

For graph consistent DAGs

and , no slot can be directly marked as on , and indirectly marked as on Proof by Contradiction:

Assume a slot

is directly marked as on and indirectly marked as on . A set of blocks on accounting for a supermajority of voting power from must each observe a certificate pattern for in their causal history (commit pattern), and block on used to decide must not observe a certificate pattern in its causal history. The algorithm asserts , so its causal history must contain at least a supermajority of blocks in which are not certificates. By quorum intersection,

and must overlap on at least one slot affiliated to an honest validator. Since - Honest validators create at most 1 block for each slot

- By graph consistency, no block can both observe a certificate pattern on

, but not observe it on , therefore

We have a contradiction, and the assumption cannot be true.

-

For graph consistent DAGs

and , no slot can be marked as on and on if Proof by Contradiction:

Assume a slot

is directly marked as on and marked as on . A set of blocks on accounting for a supermajority of voting power from must include in their causal history (certificate pattern), and another set of blocks on accounting for a supermajority of voting power from must include in their causal history (certificate pattern). By quorum intersection,

and must overlap on at least one slot affiliated to an honest validator. Since - Honest validators create at most 1 block for each slot

- A block can vote for at most 1 block for any slot

- By graph consistency, no block can vote for both

on and on ,

We have a contradiction, and the assumption cannot be true.

-

For graph consistent DAGs

and , no slot can be indirectly marked as on , and indirectly marked as on Proof by Contradiction:

Assume a slot

is indirectly marked as on and indirectly marked as on . The decision must depend on some on and must depend on some on . By graph consistency,

, else it would be impossible to reach two different decision for slot . Then by applying the previous lemma, it is immediately clear . Without loss of generality, we denote the smaller of the two slots as

, and further discuss it into two cases - If state of

is directly decided on either or , we have a contradiction, since the prior lemmas have shown that any slot that is directly decided can't have conflicting states on other graph consistant DAGs - If state of

is indirectly decided on both graphs, this brings us back to the original theorem we are trying to prove. Given that all indirectly decided slots have a lineage tracing to some directly decided slot, by induction, we conclude this also results in a contradiction

Since a contradiction is inevitable, and the assumption cannot be true.

- If state of

By this point, we've shown it to be impossible for any slot to reach different decisions across graph consistent DAGs, and therefore safety is proven.

Proof of Liveness

To discuss liveness, we start with a few important lemma. All discussions here assume we've already reached

-

If all honest validators create their block for round

within of each other, and the first leader slot of satisfies is_honest(S.validator), then all roundblocks created by honest validators will have a link to the leader block affiliated with Assume the first honest validator creates a block for round

at , and the last honest validator creates a block for round at . must be created at . Upon creation of the block, it will be immediately broadcasted to all other validators, and takes at most till receival, in other words, all honest validators receive by , which is bounded by . Provided , the earliest an honest validator timeout while waiting for is . This allows us to conclude that all blocks created by honest validators for must have a link to . -

If there exists 2 consecutive rounds

and , where for both rounds, the first leader slot satisfies is_honest(slot.validator), and all honest validators create their block withinof each other, then all blocks created by honest validators must form a certificate pattern for block associated with the first leader slot of round We discuss this in 2 parts:

-

By the previous lemma, we've already shown all round

blocks created by honest validator (a supermajority set) must have a link to . Since all round blocks must have link to a supermajority set of round blocks, by quorum intersection, they must have link to at least 1 round block created by an honest validator, and therefore must have a link to . The same argument can be recursively applied to blocks from round . With , , and the lemma is proven. -

By the previous lemma, we know all round

blocks created by honest validators must have a link to , and thus all the honest validator must wait for a supermajority of votes on round . Assuming the first honest validator creates a block for round at , we also know the blocks created by any honest validators will be recieved by all other honest validators latest by , which comes before the round timeout of any honest validator. Combining these observations, we can conclude that assuming a round block created by an honest validator does not have a certificate pattern for (i.e. a timeout occurred), it must have links to all round blocks created by honest validators. This is of course a contradiction, since round blocks created by honest validators form a supermajority set, and thus we've proven the lemma.

-

-

If there exists

consecutive rounds [ , , ..., ], where for each round, the first leader slot satisfies is_honest(slot.validator), and all honest validators create their block withinof each other. Upon all honest validators creating their blocks for , the state of all slots where will be decided, and block finalization must happen By the previous lemma, any block

affiliated with the first leader slot for the must be certified by all blocks created by honest validators. In other words, upon all honest validators creating their block, must have certificate patterns from a supermajority set of blocks, and therefore have a commit pattern. This results in being directly marked as . Upon all honest validators creating their round

block, they must have created blocks for all rounds , therefore, the first leader slot of round will all be marked as . Since the first leader slot of each is marked as , the states for all slots in can now be indirectly decided. Recursively applying the indirect decision logic, all slots where will be decided. Since all

are decided, and is marked as , the algorithm mandates and its causal history will be finalized, concluding our proof.

Key Breaking Point: View-Sync via FastForward

The previous section has proven liveness when

- Honest validators are sufficiently synchronized after

- The first leader slots for

consecutive rounds satisfy is_honest(slot.validator)

While the second condition is expected to happen every constant rounds (provided leader slot are sampled randomly with respect to each validator's voting power), the first condition appears to be non-trivial. The problem we're dealing with, in fact, is a common problem among Partially Synchronous consensus algorithms, and is often referred to as the view-sync problem.

To tackle this problem, many modern consensus algorithms adopt a separate algorithm to facilitate speedy synchronization, and Sui's Mysticeti-C is no exception.

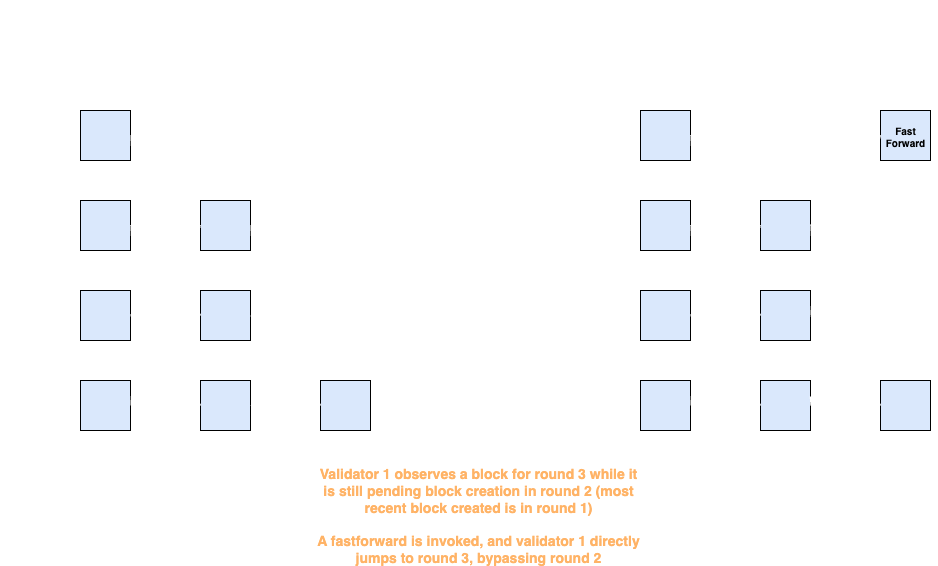

:: PYTHON1def receive_block(self, block): 2 ... 3 if block.round > self.store.pending_round: 4 self.store.pending_round = block.round 5 self.clear_timer() 6 ... 7 8def clear_timer(self): 9 self.timeout = True 10 self.pause_timeout_handler()

The algorithm is pretty simple, whenever a block

A visualization of fastforward in action is shown in the diagram:

Fastforwarding is a battletested and proven technique used in various consensus algorithms, notably, in chain-based consensus algorithms such as Jolteon. Unfortunately, adapting a know technique to a new algorithm is not always trivial. In the case with Sui's Mysticeti-C, it unwittingly introduced a liveness failure bug.

Expoiting Sui's Mysticeti-C

The usual justification of FastForward algorithms is that when there is clear evidence that some honest validators have already moved past round

The catch however, lies in the statement which does a lot of heavylifting:

some honest validators have already moved past some round

and no longer accepts messages from round

Mysticeti-C's fastforward implementation does not meet this criteria. For the sake of clarity, let's be more precise on what can be inferred when a block is received:

- A valid round

block proves a validator has received a supermajority of round blocks - A valid round

block serves as a testimony for its parent round leader blocks - The supermajority of round

blocks testified linked by the round block each serves as a testimony for their parent round leader blocks

From these properties, we can observe that a round

To put it even more directly, a round

The intuition outlined in the previous section hints toward FastForward breaking liveness, but talk is cheap, let's try to construct an attack strategy that works against Sui's Mysticeti-C.

We'll work under the following setup:

- There are 7 validators in total, each with 1 unit of voting power. 2 of the validators are byzantine and controlled by the attacker

- The attack is carried out after reaching

, so the network can be treated as a synchronous one, where maximum message delay is a known - The attacker may delay messages between honest validators, as long as it doesn't violate synchrony assumptions, and deliver messages within

of it being sent - The minimum time it takes to send a message between any two validator is a infinitesimally small

Now to the attack:

-

Assuming we start in round

, all validators are in perfect synchrony (create round block at the exact same time ), and all round block votes for round blocks. The attacker assigns roles to each validator based on the following: - The validators of the first leader slots of rounds

, , are respectively assigned roles , , . These 3 validators are allowed to overlap - One of the 2 byzantine validator which is not

is chosen to be the acting adversary - Choose exactly

validators are chosen to be the victims , in our setup, there will be 2 victims - Remaining validators are assigned the normal roles

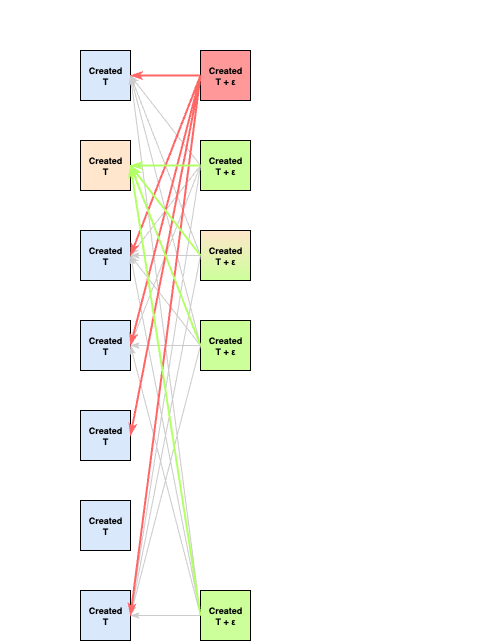

The global accumulated DAG view that includes all blocks known by any validator is shown in the diagram:

We assume the validators haven't seen each other's round R block yet (aside from the one it created itself).

- The validators of the first leader slots of rounds

-

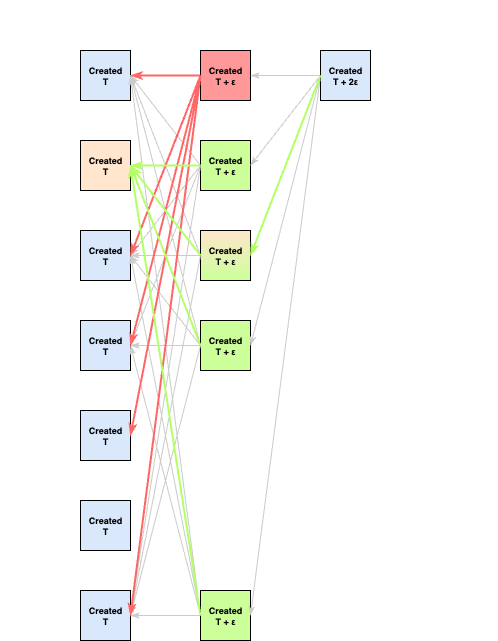

Upon creating their round

blocks, each validator broadcasts their block. The attacker delivers blocks to non-victim validators immediately, but withhold blocks delivered to the victim validators. As a result, all non-victim validators see a supermajority of round blocks by , within which includes the round leader block, as well as a supermajority of votes for the round leader block, and create their round block. Notably, the acting adversary intentionally excludes the 's round block from its round block.parent.The round

blocks are once again, delivered freely between all non-victim validators, so all non-victim validators share this local DAG view at the end of this stage.

While the honest non-victim validators have received a supermajority of round

blocks, they cannot create their round block yet since they've observed the round leader block, but haven't gathered enough votes for it yet. -

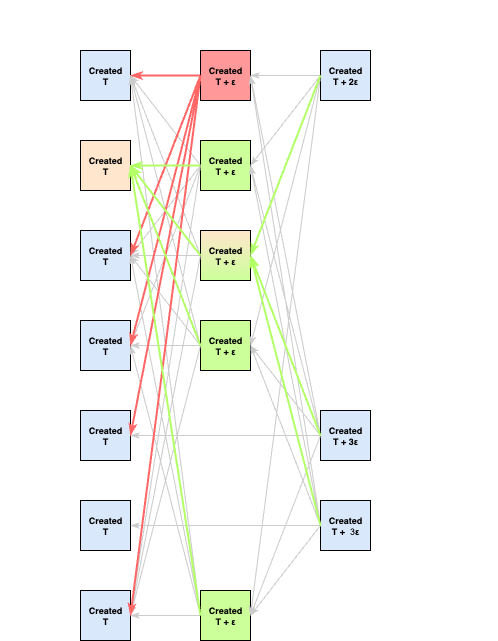

The acting adversary

, however, may disregard any rules. It immediately creates its round blocks based off the supermajority of round blocks after receiving them at . The acting adversaries local DAG view now looks like this:

-

Upon creating the round

block, the acting adversary sends it to the victims, which results in all victims fastforwarding to round , and creating their blocks for round , and broadcasts it. After their round

blocks are received by all validators, the local DAG view of all validators are once again unified:

At this point, fastforward has already failed to serve its purpose, which is to satisfy the precondition of having all honest validators create blocks in synchrony. The remainder of the exploit strategy will now focus on showing the attack can be executed perpetually.

-

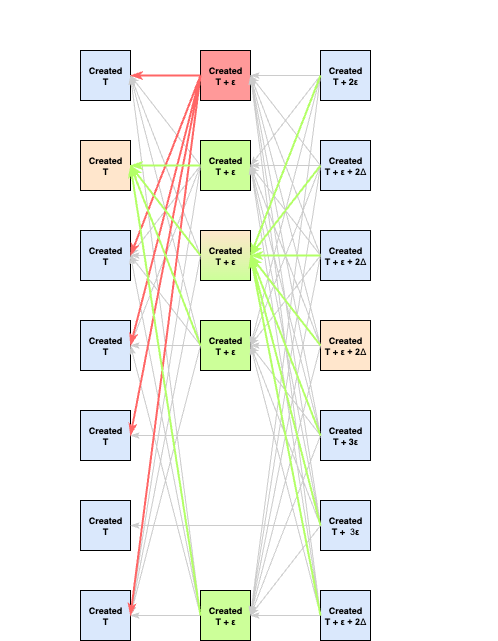

By

, all non-victim honest validators will have timeout on the round wait, and create their blocks for the round. The attacker delivers these blocks at the exact same time to all validators.

Notably, all validators will receive a supermajority of round

block earliest at . -

The round

blocks include 's round block, and they all have links to the 's round block, no additional timeout for is needed upon receiving a supermajority of round blocks. Therefore all validators create their round block at exactly . This is the global DAG view after the creation of round

blocks:

This brings us back to the original state, where all validators are perfectly synced, and all round

blocks have a link to the round leader block.

The strategy can be easily extended to different setups (e.g.

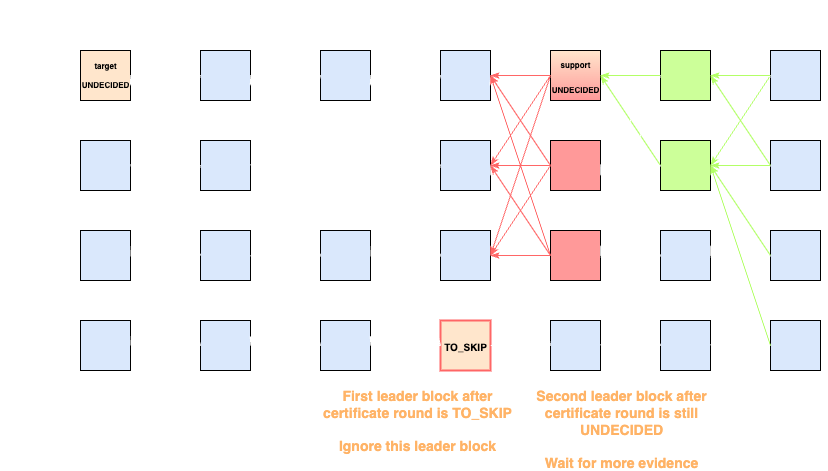

At this point, it becomes clear that the attack can be executed repeatedly every three rounds. In other words, the attacker can indefinitely prevent the leader slots of rounds satisfying

Fortunately for us (and unfortunately for the developers), indirect decisions are also impossible: determining the indirect state of any round

Since leader slots must be committed in order, and the first leader slot of

Hence we have a liveness failure. Fortunately, although an adversary can easily control two validators, the attack is still impractical, as it requires the attacker to exert precise control over message delivery delays.

Nonetheless, we were able to reproduce the scenario in a controlled environment, demonstrating the existence of this theoretical flaw.

This POC video clip is a recording of the attack in progress in a controlled environment. One can see the block transmission pattern follows the general attack idea previously described, and finalization stops after the first 3 rounds

Interestingly, the exact same bug exists in Partially Synchronous Bullshark (albeit requiring a slightly different approach to exploit), meaning Fastforward misuse in DAG-based consensus algorithms dates back to at least 2022, and has existed in the wild for more then 3 years. Out of curiosity, we also did a quick skim over the original paper's experimental code, as well as Sui and Aptos' implementation of Bullshark, and believe all these implementation are in fact vulnerable. Luckily, both Sui and Aptos has deprecated Bullshark, so these issues no longer have any impact on the two blockchains.

Final Thoughts

Sui's consensus research team is among the best in the space, and constantly publishes state-of-the-art researches. Even for a cracked team like this, occasionally there will still be oversights in algorithm design. This once again shows how complex consensus algorithms are, and even well-researched techniques like fastforwarding may turn out to be dangerous

Sui's team was fast to acknowledge the bug after we wrote a PoC against the mainnet-v1.48.4 release reported it in mid 2025. Due to the extremely high attack bar, both parties agree that an attack in unlikely. Regardless of the likelihood, the Sui team still promised to patch the issue, which testifies for their diligence and care for security.

There are a number of new blockchains considering DAG-based algorithms, particularly Bullshark, as their consensus protocol. If that’s on your roadmap, now is the right time to contact us—these protocols have security nuances that shouldn’t be overlooked.

Consensus algorithms are the cornerstone of blockchain, often treated as if they’re 100% secure. But at Anatomist Security, we break the unbreakable. Through deep technical research and rigorous audits, we uncover vulnerabilities in places most teams never think to look.

If you want your protocol, implementation, or design reviewed by researchers who live and breathe this stuff, reach out to us at X or Telegram. Let’s secure your project before someone else breaks it.